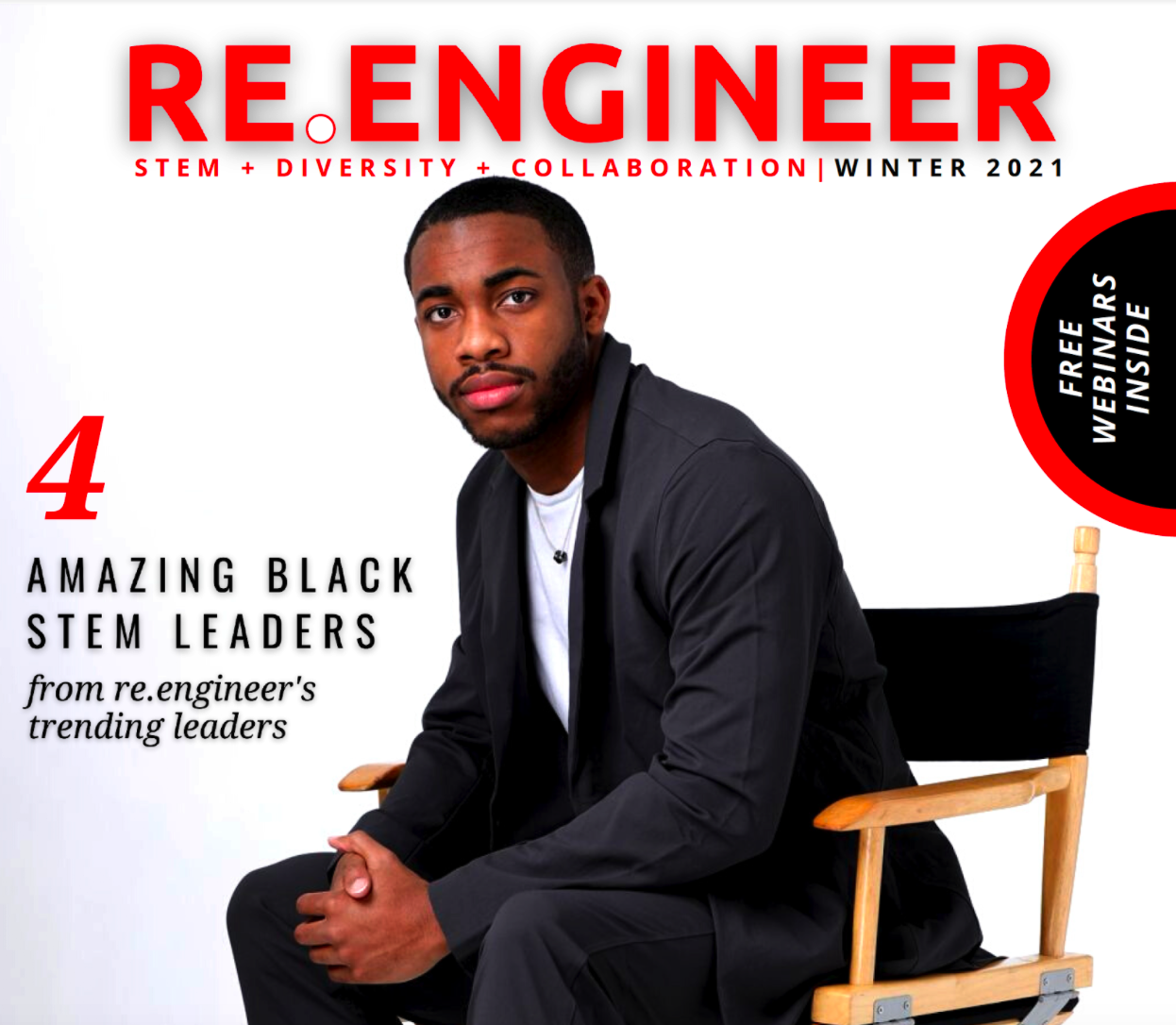

As an engineer, Shadrach Stephens has a passion for creating value. As the founder of Re.engineer magazine, he wants to create value for the entire African-American community by telling the stories of superheroes of STEM who look just like them.

In his current role as Global Improvement Leader and Reliability Director at Dow Inc., Stephens supports capital and reliability improvements for 15 sites and $6B of physical assets globally. Augury Sales Development Representative Nick Seabrook sat down with Stephens to discuss his engineering career, how to get more young people into STEM and why Dr. Martin Luther King is his innovation inspiration.

How did Re.engineer start?

Where Re.engineer started is how can we tell the stories (of STEM leaders of color) so that the next generation can see that they can be just like these people in the magazine?

People like Nicholas Benjamin, a Payload Operations Director at NASA, who is leading a tremendous program! And he’s got all of these other entrepreneurial activities on the side and he produces music. There are people out there in this nation that are doing outstanding work and it’s a shame that we’re not telling their stories. I’ve been in STEM for over 20 years and I don’t hear those stories. Unless you try to track people down, they’re not visibly out there.

And shame on me, right? Because if I look at my career, the first half of it, I spent most of my time with my head down trying to do a great job. I really hadn’t done the second half, which is to reach out and create this bridge for that next generation. So that’s what we’ve been focused on in Re.engineer. People need to know that there are successful people that look like them that are very willing to give back and help them cross that bridge.

How did you get into engineering?

My dad actually worked for Dow Chemical. He was a process automation technologist. And we always joke about how one of the reasons he’s not an engineer is because he had me. He went to Southern University in Baton Rouge just like I did and just about going into his sophomore year, he got married and had me, his first kid. He was also doing an internship with Dow in Baton Rouge and he decided not to finish up his degree but to start a family.

He used to come home with little pet projects. He used to go to Radio Shack and buy these electronics kits with the resistors and the capacitors and he would challenge me to do one of the projects. That was my extra curricular activity and so I gained an interest in problem solving. Also, pre-9/11 you used to be able to bring your family members or friends into the manufacturing plant so at a very young age, I saw what a chemical plant looked like. I saw motors and pumps. I saw control systems. I got exposure to that very early on.

There’s about 10 people that I know — I count immediate family members, cousins, uncles, even friends of the family — that were engineers. When I was a young kid I could look up to them. So I’ve always had that influence around me. I had those examples, those mentors, so I’m very fortunate.

But the root of it was I wanted to obtain a degree in four years and make the most salary from it. I was thinking I wanna get out of school as quick as I can so I can get my own place, I can get established, and I can start my life. I’ve been in manufacturing and engineering for about 20 years and I absolutely love it.

What would you say has changed the most since you got involved into the business?

The most immediate thing that comes to mind is the people around me. I started in Dow as an instrumentation engineer and at that time we might have had about 10 or 12 instrumentation and reliability engineers that supported the plants down in Freeport. And if I look to today, the number of skilled people in the discipline has been significantly reduced either through involuntary or voluntary retirement.

If you look at the baby boomer population, they’re starting to retire, right? And I think especially around the pandemic, we’ve seen a number of these folks retire even earlier than anticipated. So there’s more of a demand for the next generation of technologists and engineers to really step up and carry the torch.

There are about 71 million open STEM jobs in the U.S. alone. Over the last 15 to 20 years, the number of black students getting college degrees is virtually flat, but the number of STEM graduates is going down. So the students are not really aspiring to go into those disciplines and I think one of the reasons why is we’re not as visible and sharing what kind of success you can have in a career if you choose STEM.

What does it mean to you to be a person of color who is a leader in the engineering field?

By no means am I comparing myself to this person I’m about to mention, but I look up to Dr. Martin Luther King for his innovation. He wasn’t in engineering so we’re not talking about technology, but he had to lead, not just people that were close to him, but he had to lead the country towards making a very drastic improvement in civil rights. And for me that takes a lot of foresight and innovation.

And so for me, as an African-American leader, I wanna make sure that I have some of those same competencies built and that I have a long-term vision and strategy, not just for myself and my family, but for how the next generation is going to really drive success for our demographic. One of the reasons why our focus is on STEM is not just because that’s my background, but because you can earn a significant living by having a STEM degree and I think that’s our way to really drive financial empowerment for our community.

Everybody wants to be a million dollar entrepreneur, right? Everybody wants to be Le Bron or Lil Wayne. But the reality is that a fraction of a percent of those people are going to be successful. Not to take anything away from somebody’s dream, but I think we have a higher probability of success if we can gear our young people towards the STEM discipline.

How can we create more diverse teams in engineering?

An African-American engineering leader hired me into Dow. He moved on and then the next person in charge of that organization was another African-American leader. I’ve been blessed to have these mentors and leaders in my career that have helped to curate my success. One of our vice presidents is African-American. I look up to him as my possibility, just because he’s in that role.

Within about six years of working with Dow I became a people leader, and I’ve been in three different people leader roles. I’ve always tried to make sure I had a very diverse and inclusive organization. And if I look at my peer group who are also African-American leaders, they’re doing the same thing. They have some of the most diverse talent in their organizations. You got to have more diverse leaders. More diverse leaders equals more diverse organizations.

I look at some of the most diverse teams that I’ve ever worked on, not necessarily by their race, but by their background and their experience, those were some of the most magical times I’ve had in my career because diversity breeds creativity and innovation.

What is your advice for young engineers?

Collaboration is the next generation of innovation. No matter what the technology I’ve worked on to try to drive improvement, it’s always been a collaborative effort.

As a young engineer, I used to sit on the shop floor and watch and listen to technicians and craftsmen do their job. My first manufacturing job out of college, I worked for Carrier and I actually spent more time with the operators than with the engineers. If you listen enough to them, they will tell you what innovation is needed, because they’ll tell you their problems.

So if I can give any advice to a young engineer, it would be to listen more than you speak and go soak up that thirty or forty plus years of experience because they just want somebody to listen to them and then go execute. And as you execute, give them the recognition. Because, you know, those ideas, those great suggestions, really belong to the owners.

Want to learn more? Just reach out and contact us!